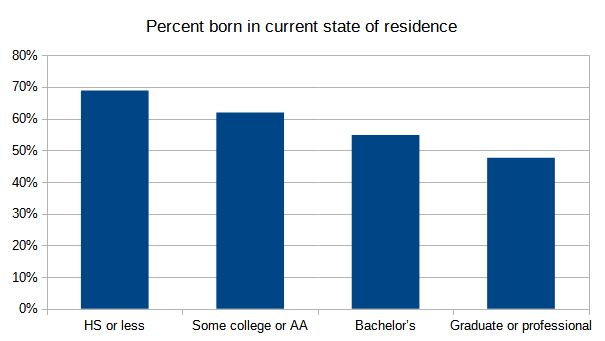

Let’s think about how education level affects mobility. Here’s a chart that shows the percentage of adults (25 years or older, born in the US) who live in the state where they were born:

The categories are:

- High School diploma or less

- Associates degree, or some college

- Bachelor’s degree

- Post-graduate or professional degree

From the chart it’s apparent that the more education you have, the more likely you will live in a state other than the one you were born in. I can see a few reasons for this. 1) Education expands job opportunities, some of which might be in other states. 2) Education expands horizons, exposing you to new possibilities. 3) Gravity: you might go to a college or graduate school in a different state, and just stay there afterwards.

The trend is definitive, but it isn’t huge. Even with post-graduate degrees, nearly half of adults live in the state they were born in.

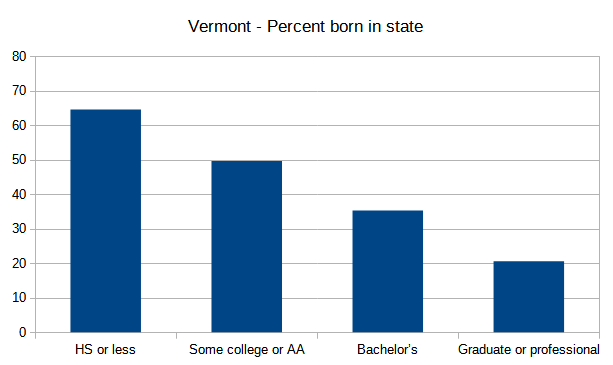

At the state-by-state level, the trend is still there: in each state, the higher the education, the less likely you will reside where you were born. But there are some interesting variations. First, let’s look at states with the steepest ‘drop-offs’. That is, as education rises the chances that you were born in that state drops significantly. (Remember, this data is relative to the current state of residence). The state that tops this list is Vermont:

In Vermont, 65% of those with a high-school diploma were born there. But only 20% of those with graduate degrees were born there. Why? That’s a good question. There are two possible factors, which the data don’t distinguish between: people born in Vermont who get a graduate degree and move out, and people born elsewhere who get a graduate degree and move in. It’s probably a combination of both, but, based on Vermont’s economy (agriculture, manufacturing, tourism) and lack of major universities, I lean more toward the former. The state just doesn’t need as many highly-educated citizens as it produces.

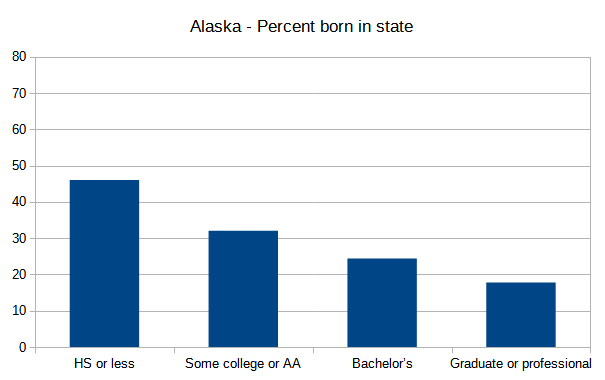

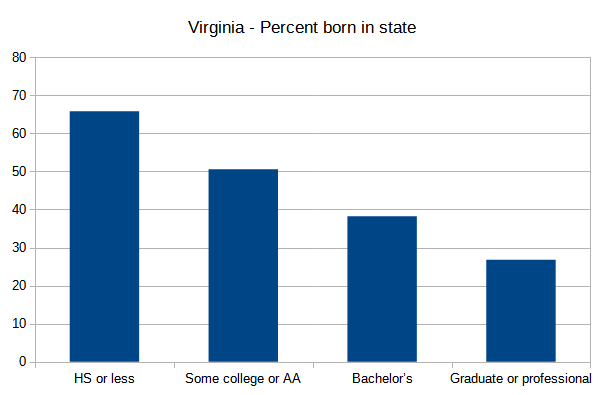

It gets puzzling looking at the next two states with the highest ‘drop-offs’:

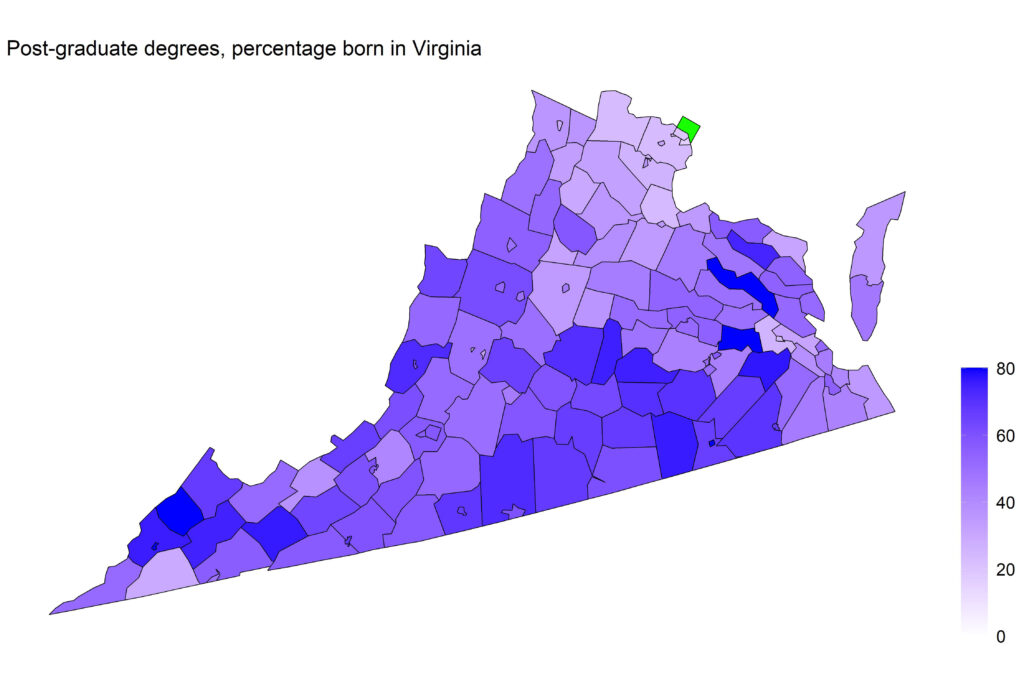

Vermont, Alaska, and Virginia don’t have much in common, but for some reason their highly-educated residents tend to come from other states. Maybe Virginia can be explained by proximity to Washington D.C. The nation’s capitol is a huge employment draw for those with degrees. Perhaps people from all around the US with bachelor’s or graduate degrees get a job in D.C. (e.g., in government, or lobbying) and move to Arlington and Alexandria? Let’s test that theory. Here’s a county-by-county map of Virginia that shows, for those who have a graduate degree, the percentage born in the state:

Hypothesis confirmed. That green box in the upper right is Washington D.C. In the nearby counties, most people with a graduate degree do not hail from VA. The further you get from the nation’s capitol, the higher the percentage. So that explains Virginia – the scarcity of Virginia-born degree holders is caused by the D.C. area getting flooded with highly-educated workers from other parts of the country.

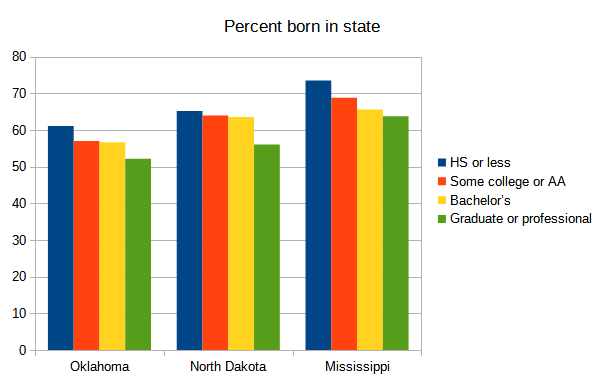

On the other end the the spectrum are states with the smallest drop-offs. These states still have a decline in birth-state residency as education increases, but it is slight. The three states with the smallest declines are shown below:

In these states, the probability of remaining in the state you were born in doesn’t change much with education level. At this point you’re probably thinking, ah ha, these states have several things in common: low population, rural, no big cities, no major centers of education, vote Republican. Fair enough. But, but what about the next two on the list:

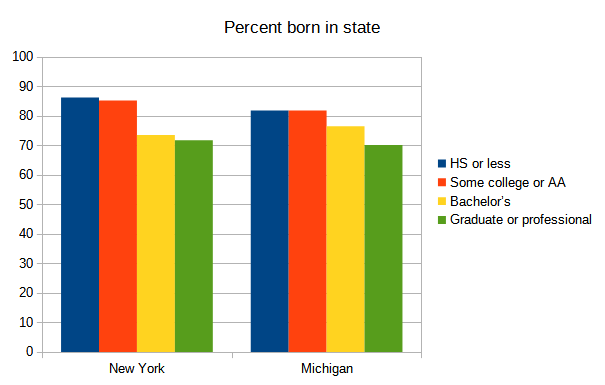

New York and Michigan are very different than the other three states: they are big states, with urban populations, and significant centers of education, strong or lean Democratic. Yet, like the other three, people born there tend to stay there, regardless of education level.

What’s the explanation? Your guess is as good as mine.