This one is part recollection, part historical sociology, with some number crunching at the end.

When I was a kid, in my pre-teen years, I listened to KGB-AM radio in San Diego. It was a typical top-40 AM radio station (hey, I was 10 years old).

Like other stations of this ilk, they had contests of various flavors. One I remember was a “cash call” contest. Roughly, it worked like this: Several times a day the DJ would announce the “cash call” value. It was always a non-rounded amount of money, for example, $124.72. Over the course of the day, the DJ would make calls to randomly selected households. If the person answering the phone knew the exact cash amount, they would win it. The amount changed every once in a while, always incrementing upward slightly. They used a non-rounded value was to make it hard to guess the total.

Clearly the contest was designed to keep you listening to the station all the time, since the cash call value could change at any moment. I don’t recall how frequently it changed; maybe a couple of times a day? This was a different era (1968-1971). Before streaming services, before iPods, even before Walkmans and mix tapes. To listen to music, you either tuned in a radio station or put on an album. So the idea of leaving a radio on for hours at a time wasn’t unusual. The contest was a nudge to keep you from switching the dial.

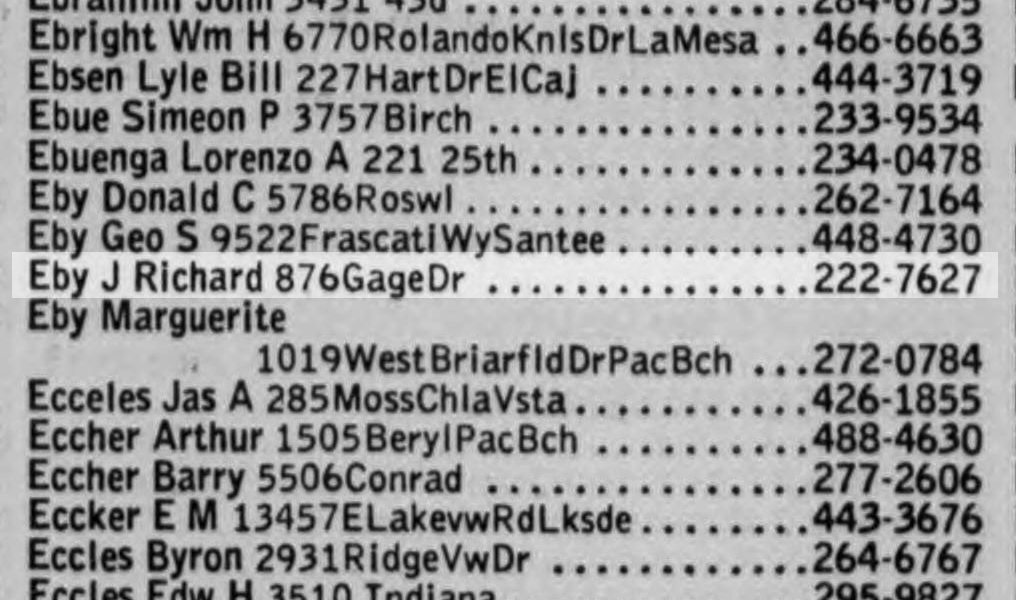

How did they choose the phone number to call? I’m pretty sure they used the phone book. Back then, there were no cell phones, and most people had a landline. Your name, address, and phone number were in the white pages. You were automatically listed, unless you paid extra to get an unlisted number (about a dollar a month; adjusted for inflation, that works out to ~$100/year in today’s money). Most people didn’t bother to be unlisted – telemarketing wasn’t the intrusive pain that it would soon become, and it was kind of nice for causal acquaintances to be able to look up your number. Here’s an example, from the 1969 white pages for San Diego, including where I lived:

How can I confirm that they use the phone book to decide who to call? The only other option is an “opt in” mechanism, where you had to explicitly send in your name and number to be part of the contest. Three arguments against “opt in”:

- I have no recollection of any “send us your name and number” announcements on the station.

- I found documentation of similar contests of that era, encouraging people with unlisted numbers to send their number to the radio station to be eligible for the contest. This strongly implies that they were using the white pages to select contestants.

- I remember a specific incident: one time the station called the elderly next-door neighbors of a friend of mine (the DJ said something like “this cash call goes out to the R Lovell residence on Dudley Street”). There was no answer (they weren’t home), but the point is, there is no way in the world that this couple in their 60s would sign up for a contest on a teenybopper AM radio station. That is pretty strong evidence that the station was picking random names from the phone book.

So, assuming that’s the case, let’s do the numbers. It’s going to be very fuzzy here. I can’t find specific ratings for that radio station in that era, but looking at similar Arbitron reports indicates that a 10% share is a reasonable guess. ‘Share’ is defined as: of all the people who are listening to radio, what percentage are listening to that particular station. What we don’t know is, of the entire population, how many were listening to radio in the first place. Again, this was pre-internet, pre-iPods, pre-mix tapes, so listening to radio for your music was much more common than now. Let’s assume a third of the households listened to the radio. That means that 3.33% households were KGB listeners (10% share of one third).

Of those listeners, how many knew the cash call amount? At this point the numbers get really squishy. I’ll take a stab and say that maybe 10% of the listeners were hard-core enough to know the amount. So now we’re at 0.333% of San Diego households who are ready to win. Which means that 99.666% of the time, the cash call is a loser.

Using those numbers, the average number of calls needed to get a winner is 300. If the station made calls, say, eight times a day, that’s a winner every 37.5 days. That’s not too far from my recollection: winners were rare, but they did happen every month or two. So we’re in the ballpark; a contest designed this way could produce winners frequently enough to spark interest, but rarely enough not to break the station’s bank.

As I said, these numbers are pretty vague. But they pass the “sanity check” – we get a plausible result. We can never know the real numbers, but they probably weren’t that different than mine.